By Stefan Superina and Dr. Bob Bell

Canadian stereotypes are well known – we’re overly apologetic and polite, nice to a fault, and may have an unhealthy obsession with discussing the use of the notwithstanding clause and hockey trades at cocktail parties. Perhaps it’s because we spend too much time holed up in winter and simply need to get out more.

Just like Canadians, Germans come with their ascribed stereotypes as well – they’re punctual, efficient, direct, orderly, and enjoy a diet of sausage, beer and sauerkraut. However, another stereotype pertinent to this piece is that Germans have a long history of insurance to cover social and financial risks and government policies for mandating and describing how insurance works for various needs. In short, insurance is big business in Deutschland.

Chancellor Otto von Bismark introduced the world’s first social health insurance system in 1883. Before the introduction of the Health Insurance Act of 1883 that formally established compulsory insurance as social policy, craftsmen belonging to guilds in the Middle Ages advocated for insurance-based measures so that any guild member encountering financial difficulty due to illness had access to pooled funds in times of need. This notion of solidarity – whereby every guild member paid what they could and had a right to necessary compensation in catastrophe regardless of income or social status – is a fundamental tenet upon which the German healthcare system is built. Whether or not it functions well in this regard today is up for debate.

Nonetheless, it is well worth examining the German healthcare system because it has withstood the test of time for over 135 years – through world wars, global recessions, and social upheaval – and is considered to be one of the finer examples of a universal healthcare system. Similar to Medicare in Canada, the German healthcare system is under increasing stress due to an aging population and increasing burden of chronic disease. The future success of these two systems will depend on their flexibility to adapt to new challenges and demands.

An overview of German expenditures on health care

With a population of 83 million, total spending on health as a percentage of GDP is higher in Germany than Canada (11.3% vs. 10.3%). As well, the Germans commit more than Canada on public spending on health as a percentage of GDP (8.7% vs. 7.4%) and mean spending on health care per capita ($5,182 vs. $4,641).

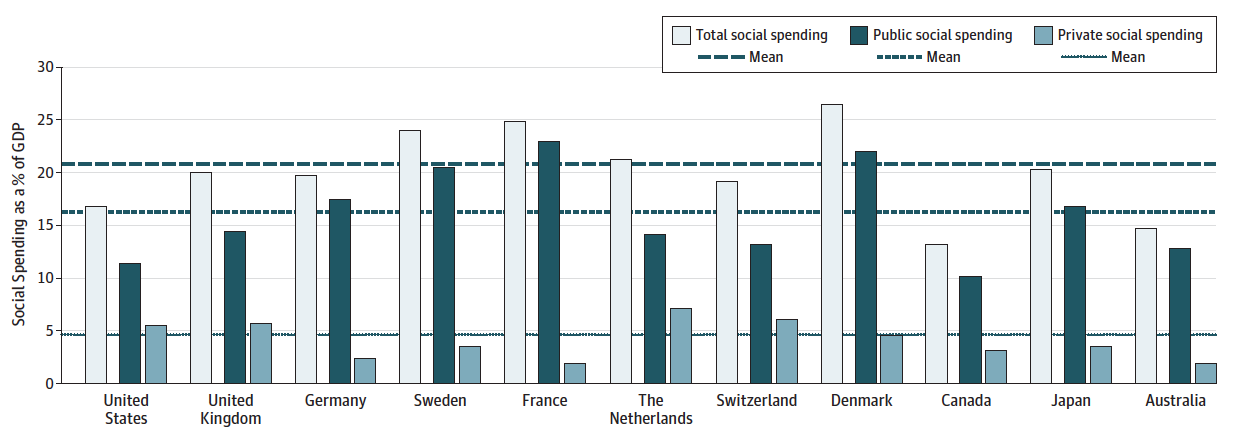

As we have previously mentioned, Canada falls far short of other wealthy countries when it comes to social spending as a percentage of GDP. As seen in the bar graph, Canada commits less than any of our peers to underlying social determinants of health that are recognized as being strong contributors to overall health care outcomes. And this tendency to lower spending may be accelerating.

For example, recent Ontario government cuts to programs such as legal aid only serve to compound existing issues of health equity and access. As Dr. Gary Bloch notes in his commentary on legal aid cuts: “As with most cuts to essential social services, policies that look like savings from one angle often cost us more, in increased health costs and lost productivity.”

Social Spending as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product. Source: Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries.

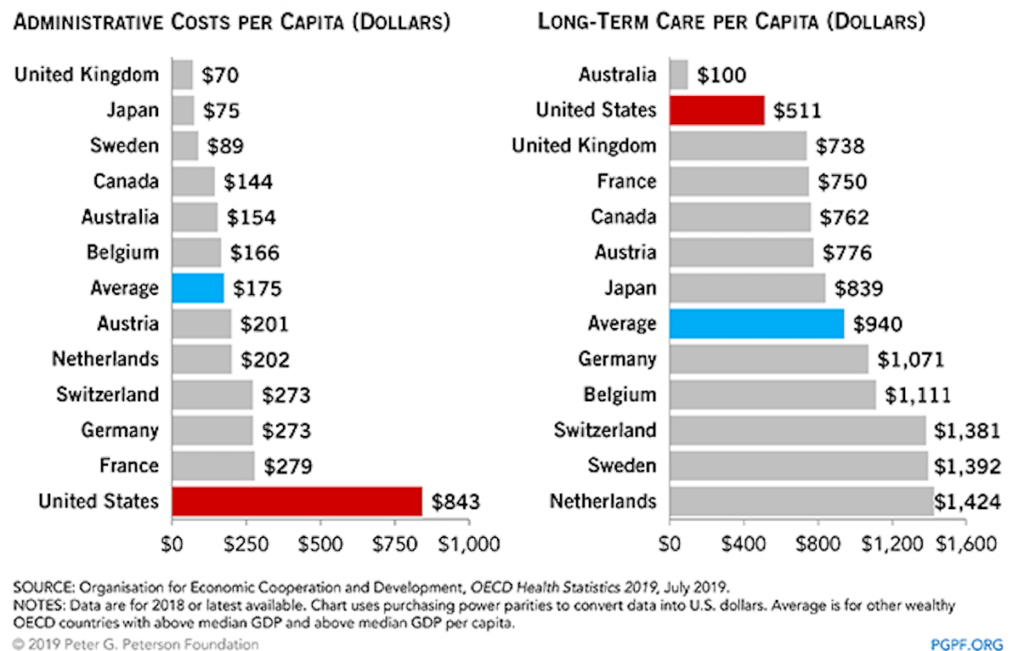

Recently, Ontario health care restructuring has focused on the elimination of bureaucracy. It is interesting to note that Germany spends more than Canada on governance and administration of their healthcare system (5% vs. 3%) as a percentage of total national health expenditures. It is worth noting that the highest spending countries with respect to administrative costs per capita below are all dependent on similar models of market-based health insurance.

Compulsory Insurance

Everyone is required to purchase health insurance in Germany, as well as accident insurance, pension insurance, unemployment insurance, and long-term care insurance – commonly known as the five main mandatory branches of insurance in the German social code. The system is rooted in overarching principles of solidarity and self-governance – that is everyone has equal right to receive support, premiums are calculated according to income, and organization and financing of medical care is the responsibility of self-governing bodies in the healthcare system. The Federal Joint Committee is an important payer-provider joint entity that is responsible for defining rules around access and distribution of health and social care, benefits coverage, and coordination of care.

Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) in Germany covers approximately 88% of the population and is financed primarily through individual premiums based on income. It is the default form of insurance for every German below a certain income threshold – €56,250 ($82,491 CDN) in 2016. Premiums are split evenly between employer/employee and are funded through payroll taxes (in 2016, this amount was set at 14.6% of gross wages). Sickness Funds (insurance offerings) were introduced in 1993 as a means to provide choice among payers in the SHI market. According to the Commonwealth Fund’s healthcare system profile of Germany, there are 124 competing Sickness Funds.

Any individual earning above the income threshold is given the option to opt out of the SHI public insurance system and shop around in the Private Health Insurance (PHI) market, which covers approximately 12% of the German population. The PHI option also applies to self-employed individuals and civil servants. Co-payments (also known as tariffs) for accessing health care services are present in both the public and private system and vary according to one’s plan.

Importantly, SHI funds are only allowed to vary premiums on a client’s income, whereas PHI suppliers set premiums according to individual health risk assessment – these PHI premiums fluctuate substantially based on risk and service provision.

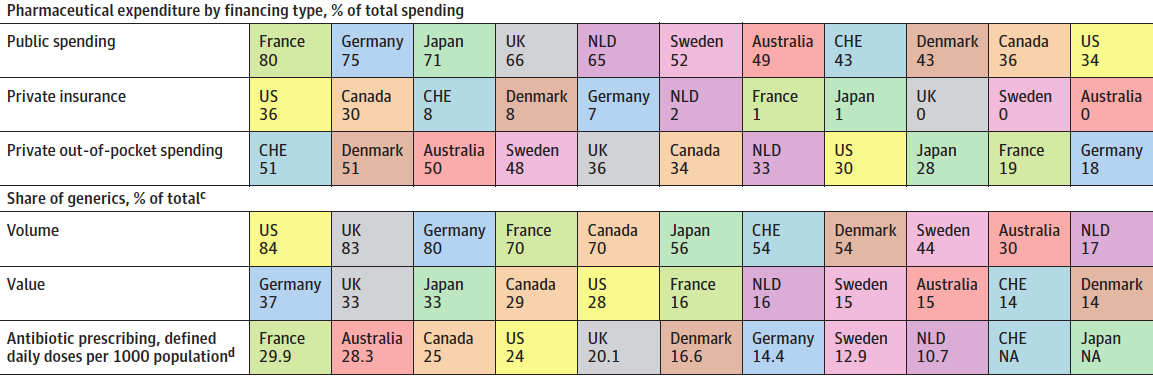

Unlike in Canada, comprehensive drug and dental coverage is offered through both the SHI and PHI markets. This is an important distinction when examining issues of access and equity in the Canadian healthcare system. With respect to pharmaceutical expenditures by financing type as a percentage of total spending, Canadians spend far more on private out-of-pocket spending on drugs (34%) than Germany (18%). As well, private insurance in the Canadian market to cover drug expenditures accounts for 30% of costs (second only to the US), whereas this only accounts for 7% of pharmaceutical expenditures in Germany. Finally, it should be noted that Germany has some of the highest penetration of generic drugs in the pharmaceutical market. The share of generics (% of total) in Germany accounts for 80% of the volume and 37% of total value – Canada is 70% and 29%, respectively. This demonstrates why Canada could benefit from universal pharmacare.

Source: Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries.

Delivery of Care

Germany has more practicing physicians than Canada (4.2/1000 vs. 2.6/1000) as well as nurses (13/1000 vs 9.5). According to Papanicolas et al., generalist physicians, specialist physicians, and nurses in Germany are remunerated at rates similar to those enjoyed by Canadian professionals. This comparison may not be entirely accurate because it probably does not take into account individual practice expenses for self-employed physicians. As well, there is ample opportunity for German physicians to supplement their income in the private sector that is likely not accounted for in this comparison.

Busse et al. provide an excellent overview in The Lancet of the delivery of healthcare in Germany since the introduction of the Health Insurance Act. The authors note that a prominent feature of the German healthcare system is the traditional separation of the outpatient and inpatient sector. Hospitals are mainly restricted to inpatient care without a major focus on ambulatory clinics.

GPs and specialists in the ambulatory care setting contract with Sickness Funds, with the majority of physicians in the ambulatory setting opting to work in private clinics (60%). Compensation is on a fee-for-service basis predicated upon a uniform fee schedule that is negotiated between the Sickness Funds and the physicians.

Various bonuses are built into the system to incentivize private ambulatory clinics to enroll and care for patients as part of comprehensive disease management programs. According to Busse et al. “FFS payments are limited to covering a predefined maximum number of patients per practice and reimbursement points per patients, setting thresholds on the number of patients and of treatments per patient for which a physician can be reimbursed. For the treatment of private patients, GPs and specialists also get FFS, but the private tariffs (co-pays) are usually higher than the tariffs in the SHI uniform fee schedule.”

There are also a number of multispecialty clinics in Germany that are staffed by salaried physicians. The hospital sector is composed of a mix of public hospitals, private non-profit hospitals, and for-profit hospitals. Hospitals are staffed primarily by salaried doctors with senior physicians being allowed to treat privately insured patient on a FFS basis. After-hours care is available in both the inpatient/outpatient setting and is variable according to the insurance plan one is enrolled in.

Busse et al. cite two fundamental problems with care delivery in Germany that should be considered in the context of Ontario Health Teams that may rely on provider organizations to plan, deliver and provide oversight of care:

- The problem of care over-provision in Germany is especially challenging in the context of self-governing actors.

- The practice of setting broad policy objectives at the federal level and leaving it to self-governing actors to work out the specifics might need to be reassessed.

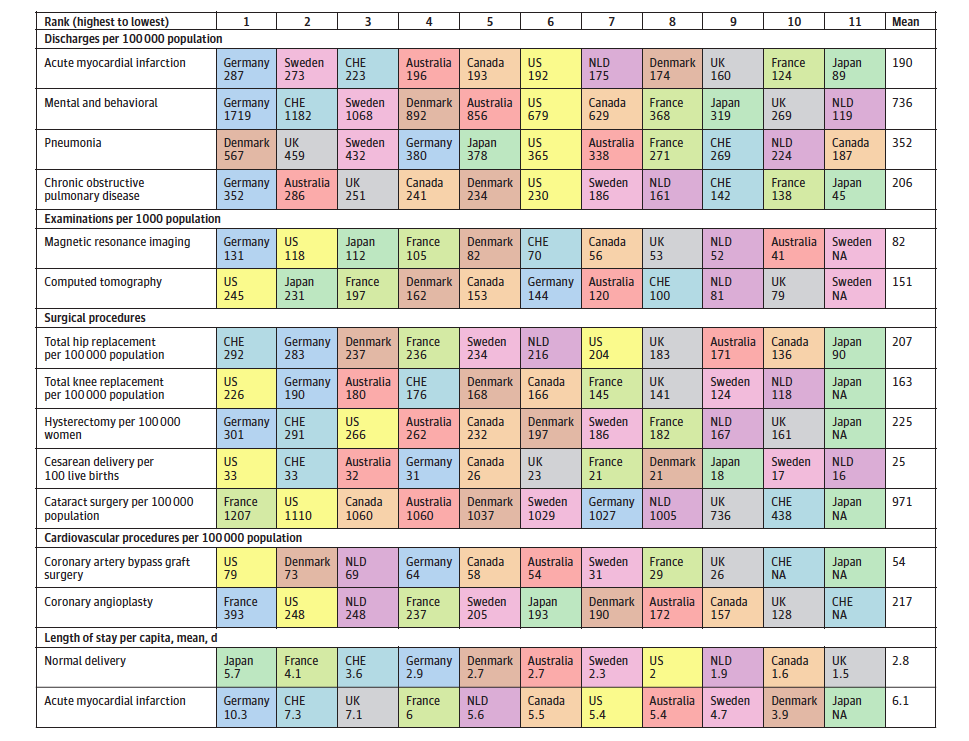

For further evidence of how the German model of care delivery can potentially lead to overuse and exploitation of unnecessary testing and treatment, we can simply look to utilization data published by Papanicolas et al. to draw some conclusions. Germany ranks at the top or near the top for almost every utilization measure. It should also be noted that Germany has more hospital beds/1000 population (8.2) than any other country excepting Japan (13.2). Does loose governance and oversight of the health insurance/provider market in Germany allow providers to carry out unnecessary care for financial gain?

Health care utilization. Source: Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries.

In order to address inappropriate utilization, the concept of selective contracting was introduced in Germany to provide gatekeeping measures. In effect, these selective contracts were put in place between physicians and sickness funds to encourage more coordination of care and to prevent individuals from simply bypassing primary care providers to see a specialist. Perhaps similar to the original intent of family health models introduced in Ontario, selective contracting was introduced as a means to strengthen the role of GP’s in the healthcare system.

Disease Management Programs were initially put in place as a form of selective contracting for a number of chronic diseases to better organize care in line with evidenced-based guidelines, with the idea being that more care could be delivered at the ambulatory level than in an acute care hospital setting.

Selective contracting has evolved to include Integrated Care Contracts and Gatekeeping Contracts. Sickness Funds are legally obligated to offer their members the option to enrol in such programs. In return for doing so, members accept gatekeeping before seeing a specialist and, in return, receive privileges such as exemption from copayments or shorter waiting times.

Wait times and private care in Germany

Long waiting times for health care in Canada are often the main argument used to advocate for the introduction of private care as a means to offer more rapid access and alleviate the strain on our publicly funded system. Indeed, wait times for many elective procedures in Canada are too long and put undue stress on those waiting to receive them. Many suggest we look to Germany for a solution.

The Fraser Institute for example, known for its advocacy of private care, suggests that Germany is the top performer in terms of wait times for elective surgery and that Canada’s health care wait times are the worst. However, we should carefully examine the evidence supporting these statements.

First off, as we have pointed out in other health system blogs, the Fraser Institute and other organizations advocating for private care in Canada use the Commonwealth Fund findings to support their perspective. While the Commonwealth Fund draws on a variety of valuable OECD data sources, its wait times data is overwhelmingly derived from surveys. Examining the methodology notes compiled by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the report states: The Commonwealth Fund’s 2016 International Health Policy Survey of Adults reflects patients’ experiences and perceptions among a random sample aged 18 and older in 11 countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. On page 4 of the report, one can see that Germany had the lowest total number of interviews (1,000). So, in a country of 83 million people, are we really drawing the conclusion that Germany is the best performer in terms of wait times for elective surgery based off of a sample of 1,000 people?

Clearly, a more objective lens to evaluate German wait times is required. A recent publication in Health Policy by Viberga et al. (International comparisons of waiting times in health care – Limitations and prospects) provides more details.

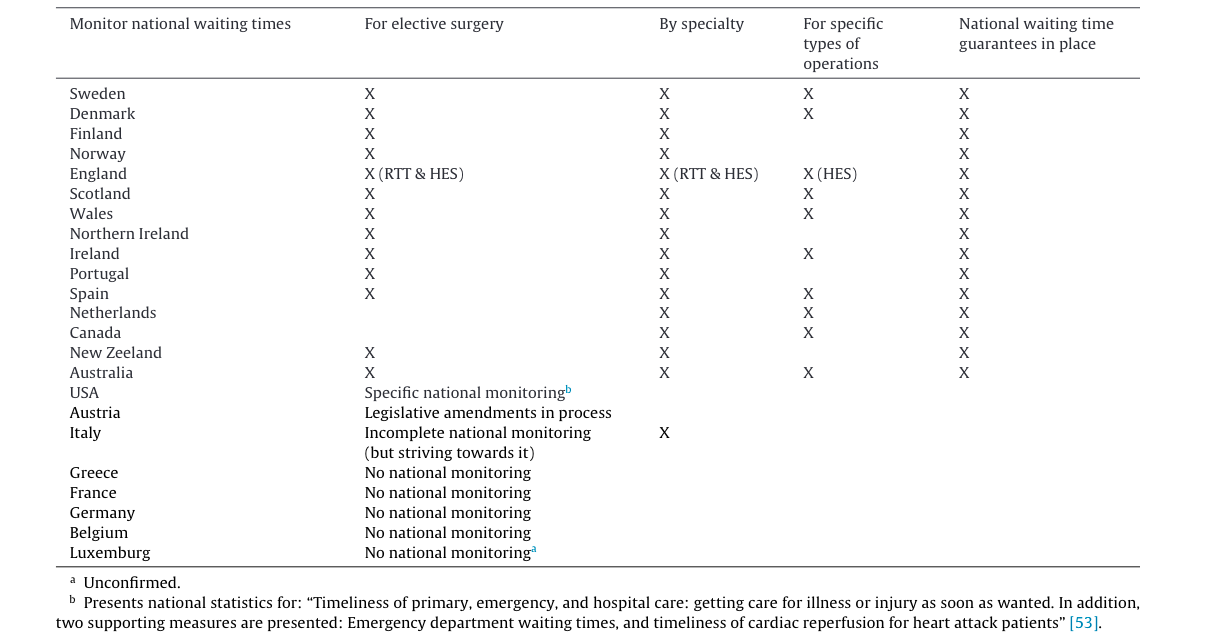

As the authors note in their findings, fifteen of the 23 countries included in the study monitor and publish national waiting time statistics – Germany was not on the list of those who published such criteria.

Countries that monitor and publish national waiting time data for elective surgery and the degree of detail at which they do so, and whether they have national waiting time guarantees.. Source: International comparisons of waiting times in health care – Limitations and prospects.

Below we have listed some interesting points the authors make with respect to those countries that do not have national waiting times criteria:

- France’s lack of national monitoring is often cited as evidence that the country has no waiting time problems. However, the large regional differences in terms of services provided and numbers of doctors have led to inequities in access.

- In Germany the debate has revolved around the fact that people who are privately insured have faster access to health care.

- In Austria, researchers have found that privately insured patients have faster access and they have refuted the notion that the country has no waiting times.

- In the United States, access to care varies with socioeconomic status and geographic area.

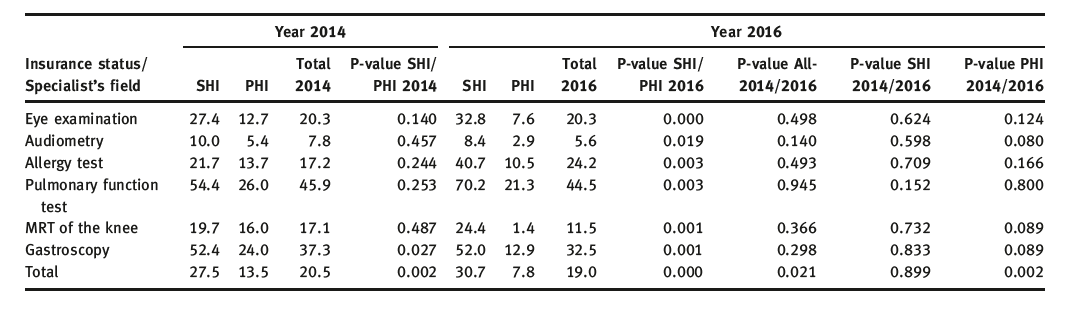

A further study on Germany that examines levels of access between the SHI and PHI markets is available. In Waiting Times for Outpatient Treatment in Germany: New Experimental Evidence from Primary Data, Heinrich et al. assess the impact of health insurance status on waiting times to evaluate whether those with private health insurance can obtain an appointment for specialized outpatient treatment faster than those with statutory health insurance.

In short, the authors examined data for six common elective outpatient procedures in Germany: eye examination (ophthalmology), audiometry (otorhinolaryngology), allergy test (allergy), pulmonary function test (respirology), MRI of the knee (diagnostic radiology) and gastroscopy (gastroenterology). In the study, physicians were contacted via telephone and an appointment for the relevant elective procedure was requested with stated type of insurance. In total, 397 appointments were made.

Source: Waiting Times for Outpatient Treatment in Germany: New Experimental Evidence from Primary Data

The authors conclude: SHI patients face higher waiting times that persist over time – with the average waiting time increasing from 28 working days in 2014 to 31 working days in 2016. In contrast, privately insured patients’ waiting time decreased significantly from 14 days in 2014 to 8 days in 2016. In relative terms, in 2014 SHI policy holders waited for an appointment on average twice as long as PHI holders; they had to wait almost 4 times as long in 2016. The differences between PHI and SHI policy holders were statistically significant in both years.

Clearly, there is preferential treatment given to those with private health insurance. There are also enormous advantages for physicians to treat private patients in Germany – reimbursement rates can be up to three times as high.

Could Canada benefit from German-style health care?

As Busse et al. note in The Lancet, an examination of data suggests that German health care may very well lead to over-provision of unnecessary services in hospital as well as primary and specialized ambulatory care. Notably, the authors state that the problem of care over-provision is especially challenging in the context of self-governing actors.

In our opinion, Canada should carefully evaluate Germany as an example of a healthcare system that we can learn from. The German system of statutory health insurance offers dental and drug coverage, and the value of German pharmaceutical provision should be considered in our current pharmacare debate. There is ample evidence that the German system leads to over-utilization of hospital resources and unnecessary testing – something that is being addressed in Canada through the implementation of Choosing Wisely Canada guidelines and attention to appropriateness by medical associations and ministries.

One important OECD figure stood out when evaluating Commonwealth Fund data comparing Canada and Germany: life expectancy at age 60 in Germany is second worst in wealthy nations, only better than the US, whereas Canada placed fourth overall in this metric.

Reflecting on Germany as an indicator of future changes in our system, one could be concerned about the direction of Ontario Health Teams (OHT). While the OHT emphasis on integrated care and improved patient navigation is important, the lack of prescribed external governance in the OHT model is worrisome – especially given the concerns regarding provider governed models in the German system. Grant LaFleche captures this concern well in the recent Ontario health care series in the Hamilton Spectator.

So what can Ontario learn from the German healthcare system? Allowing OHTs to operate with no formal governance structure in place within a loose rules environment, similar to certain instances in the German healthcare system, may lead to local policies that benefit the provider rather than coordination of local patient care. Already, many health care providers have voiced concern with respect to the ‘volunteer time’ they are being expected to contribute to the OHT process.

Who is accounting for the allocation of resources? Who is the ultimate decision maker/s in each OHT? One might expect that this will all work itself out with altruistic providers sublimating their interests, but the German experience in a loose rules environment suggests that self-interest will generally prevail.

Finally, as we draw to a close on these health system comparative blogs, it should be remembered that a recent study ranked Canada number 1 in the world for quality of life for the fourth year running. Canada scored highly in numerous metrics, including 9.6/10 for its well-developed public health system. Yes, our health system needs to evolve by increasing expenditures on social spending that support social determinants of health such as access to affordable housing, clean drinking water and healthy food.

However, we would argue that our health system does not require a fundamental system overhaul based on private health care interests. There is no objective evidence to support the notion that tiered access based on ability to pay will alleviate public wait times for care. Canadians need to be acutely aware that our publicly funded system is at risk, and that it requires both focused improvement and protection.

Perhaps most importantly, we need to ask ourselves who will economically benefit the most from the introduction of private health care in this country.