Bob Bell, MD, and Stefan Superina

Switzerland is a small but extremely wealthy country situated in the Alps in the centre of Western Europe. Although not a member of the European Union (EU), Switzerland has adopted various provisions of EU law so as to participate in the common market.

Switzerland has a population of nearly 8.5M people of whom 20 to 25% are resident foreigners, mainly from European countries. All residents of Switzerland enjoy the same health system. Switzerland’s GDP per capita is $54,000 in USD, $2000 higher than the USA and nearly $12,000 higher than Canada. Seventeen percent of the Swiss population is below the poverty line, compared to 21% in Canada and 24% in the USA.

What is LaMal?

The modern Swiss health system was started in 1996 with the passage of the Federal Law on Health Insurance or “LaMal” which responded to a fragmented system of health care being managed by 26 local “cantons”, each with different costs and quality of care.

LaMal is similar to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in that it is based on an “Individual Mandate” (everyone must purchase health insurance), and also maintains private insurers rather than a government single payer system as the basis for coverage.

LaMal differs from the ACA in that the insurers are highly regulated. They must offer insurance to everyone regardless of pre-existent condition, the price is consistent, the benefits of all basic policies are the same and the insurer may not make a profit off the basic comprehensive policy.

LaMal is also similar to the American system in that health costs are shared between public payment and the private insurance industry. The national and canton governments support health costs directly and the government also subsidizes insurance costs for up to 50% of Swiss who are on the lower income scale.

The basic policy covers ambulatory and hospital services, drug costs for a public formulary, some dental and rehab services as well as some alternative medicine.

There is a standard deductible of 300 SF annually or an extended deductible of 2500 SF which, if selected lowers the policy cost. Choice of practitioners is unlimited by the standard policy although there is an option for a lower cost insurance which limits coverage in the same fashion as a provider network of an HMO.

Coverage is portable and is neither subsidized by nor tied to employment.

Payments to providers are regulated and negotiated by the local canton and the national insurers. The government serves to equalize risk across the insurance companies by redistributing some of the premium based on risk and utilization.

How Good is Swiss Health Care?

Analysis of the quality of Swiss health care can begin with the New York Times which ran a showdown between 8 countries and selected Switzerland as the best system in the world in a bracketed competition that simulated March Madness.

The quality of care can also be assessed by what the system does not measure – wait times for surgery or other care. Similar to Germany and France, wait times are not collected in Switzerland “because they are not a problem”.

According to OECD data, life expectancy and health adjusted life expectancy amongst Swiss is marginally better than in Canada, as are maternal mortality and infant mortality. Switzerland has the highest number of doctors and nurses per capita in the wealthy world (MD/1000, 4.3 CHE vs. 2.6 CAN; RN/1000, 17 CHE vs. 9.5 CAN).

The OECD does not report on health human resource compensation. Other information however, suggests that Swiss physicians are amongst the highest paid in the world.

The Swiss system is well stocked with both acute care beds and long-term care beds when compared to Canada (hospital beds/1000, 4.6 CHE vs. 2.7 CAN; LTC 68 CHE vs. 54 CAN). Hospital overcrowding or long ER waits for admission do not seem to be a problem for the Swiss.

Switzerland has very high utilization of total joint replacement surgery, cross sectional imaging, hysterectomy and caesarian section, but a surprisingly low utilization of cataract surgery.

Perhaps not surprising for a country that serves as national headquarters for several large pharmaceutical companies, expenditure on drugs is second only to the USA and a low value of the drugs used are generic.

How Expensive is LaMal Compared to Canada?

Switzerland has the second highest expenditure on health care in the world, spending 12.4% of GDP compared to 10.3% in Canada. Remembering that Swiss GDP per capita is much higher than Canada’s, the Swiss spend $6787 USD per capita on health compared to $4641 USD in Canada.

Because of the mandatory purchase of health insurance, only 62% of Swiss health costs are funded publicly, compared to 71% in Canada.

If Canada were to adopt LaMal as structured today, publicly funded health care costs would increase by $1179 CDN per person. In Ontario, this would increase health expenditures paid though tax by about $16.5B annually (on the current base expenditure of about $63B – an increase of about 25%).

Canadians would also increase their private insurance costs by $1696 CDN per person.

Combining extra tax costs and private insurance costs ($1179 + $1696= $2875) the total increase for an average family of four (recognizing that average refers to tax rate rather than income) would be about $10,000 CDN (knowing that children have lower premiums than adults).

Does compulsory insurance disadvantage lower income citizens?

Proponents of the Swiss healthcare system suggest that it works well because it satisfies the goals of universal coverage in a regulated insurance market accompanied by lower government spending and a degree of privately managed health care. However, context is important when examining different health systems and drawing comparisons between systems.

For example, one needs to appreciate the difference in GDP/capita between Switzerland and Canada. This requires a closer examination of how compulsory insurance in Switzerland affects the economically disadvantaged to provide insight into potential pitfalls of adopting such a system in Canada.

In the Swiss healthcare system, one is free to shop around in a market for the insurance provider and policy that best suits family needs. Once secured, you pay a monthly premium that is directly proportional to the deductible (ranging from 300 SF to 2,500 SF).

For those below a certain income threshold, the Swiss government offers subsidies that vary depending on eligibility criteria set by each canton. However, this subsidy and the income threshold to qualify for it continues to be the subject of much debate in Switzerland as it may disqualify families just above the threshold. Data indicates that insurance premiums account for 12% of all disposable income for households receiving state subsidies.

Most policies cover the basic provision of care services that we receive under the public system in Canada, with supplementary insurance available for the provision of further services (dental care, glasses, orthotics, etc.) that is obtained under private employer-based plans in the Canadian system.

Insurance companies will offer policy holders a lower monthly premium in exchange for a higher deductible. For those in lower income brackets who cannot afford to pay higher monthly premiums, they will more likely opt for the lower premium/higher deductible option and cross their fingers that they don’t get sick.

If they do get sick and exceed their deductible, they would be subject to a 10% payment of any costs above this given amount, referred to as a retention fee that is limited to 700 SF a year for adults and 350 SF a year for children.

Evidence indicates that costs for premiums for compulsory insurance in Switzerland have risen at twice the rate of GDP and wages since 1996. According to an OECD report in 2017 (Health at a Glance), approximately 21% of Swiss residents reported going without medical care due to the cost of seeking it – only Poland (33%) and the US (22.3%) were higher. In fact, the high costs of health insurance premiums paid to private companies in Switzerland are reportedly the second most common cause of debt after tax.

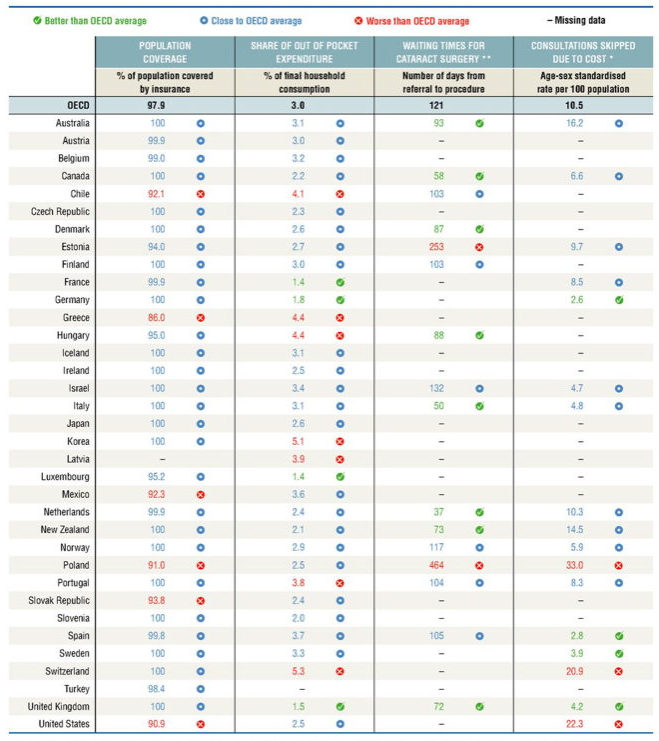

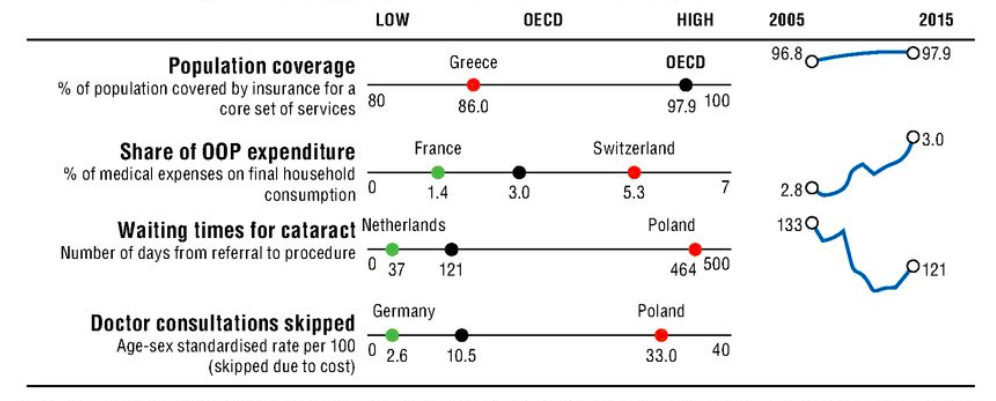

OECD Dashboard on Health Status: Approximately 21% of Swiss residents reported going without medical care due to the cost of seeking it – only Poland (33%) and the US (22.3%) were higher. Source – OECD Health at a Glance 2017.

Snapshot on access to care across the OECD: As a share of out-of-pocket expenditures, Swiss residents spend a higher amount on medical expenses as a percentage of final household consumption than most OECD countries. Source – OECD Health at a Glance 2017.

The Swiss system of mandatory insurance coverage does provide universal care and access to an excellent healthcare system. However, funding only 62% of healthcare costs through progressive tax-based revenues means that a higher proportion of basic healthcare revenues is obtained through measures that impact economically disadvantaged people.

The fact that a high proportion of Swiss citizens avoid care for economic reasons is telling. We know that about 10% of Canadians avoid taking prescription drugs for economic reasons. Both of these facts suggest that a universal, tax-based system for all medically necessary care is likely the most progressive way to fund a health system.

Image Credit: ©grigory alekhin – Alamy Stock Photo