By Stefan Superina and Dr. Bob Bell

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer is widely considered one of the seminal works in English literature. Penned between the late 1390s up until Chaucer’s death in 1400, the book is framed as a storytelling contest between a group of pilgrims en route from London to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. The winner of the contest is to be awarded a free meal upon return to London. While Chaucer intended to write over 100 stories (each pilgrim was to tell two stories on the way to Canterbury Cathedral and two each on the way back), he had only written 24 by the time he passed away. Although the characters in the Canterbury Tales are fictional – a knight, cook, nun, physician, and many more – they are meant to provide the reader with differing perspectives on customs and practices of the time that perhaps speak more broadly to social class and convention.

As we travel down under once again to examine the Canterbury health system of integrated care in New Zealand, one can’t help but wonder what tales of integrated care are being presented by the more than 150 groups that have applied to become Ontario Health Teams. Similar to the Canterbury Tales, the Ontario Health Team applicants likely resemble a whole host of characters and institutions that reflect differing perspectives on customs and practices of how health care should be delivered. They likely also reflect service provision to differing social strata based on the diversity and geographic enormity of this province.

It will be interesting to see what the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care will eventually decide on as the first successful round of applicants. And instead of being awarded a free meal, the pilgrims journeying to the ministry to make their case for the formation of an Ontario Health Team will be rewarded with the responsibility of achieving the largest structural change in Ontario health care since the introduction of Medicare.

The New Zealand Healthcare System

Before peeling back some of the layers of the Canterbury health system of integrated care, it is first appropriate to understand how health care is delivered in New Zealand.

New Zealand spends somewhat less than Canada on health care as a % of GDP – 9.4 vs. 10.3 per cent. A country consisting of two main islands, New Zealand is home to approximately 5 million people whose care is provided through a publicly financed system similar to Ontario’s. The passage of the Social Security Act in 1938 enshrined health care in New Zealand as a universal right, intended to be accessible and equitable without any barriers to access. As we have seen in our examination of other international healthcare systems that are financed through public taxation, the passage of the Social Security Act was met with opposition from doctors of the day.

Like Ontario’s Local Health Integration Networks (LHIN), the healthcare system in New Zealand is organized into 20 geographically distinct District Health Boards (DHB) established in 2000, each with their own governance board and management that is responsible for the planning and provision of services. Similar to the LHIN boards (which have now been dismantled), DHBs are often faced with a delicate balance of allocating limited public dollars to meet increasing health care demands. DHBs may also purchase services from private providers, similar to the provision of homecare services in Ontario. All DHBs are required to prepare planning and accountability documents, including an annual plan and an annual report.

As well, DHBs may purchase services from other DHB providers through what’s known as inter-district flows (IDFs). IDFs can occur for such things as hospital inpatient services, outpatient services, primary care, community pharmacy, and laboratory service. The NZ Auditor General has reviewed IDFs and found that occasionally DHBs may restrict patient access to services outside their region. This may harm the development of centres of excellence and the best use of resources in regionalization of services.

Physician Compensation in New Zealand

Physicians are compensated in New Zealand differently than in Ontario, and this must be considered when contemplating the Kiwi model of integrated care. First, primary care providers (PCPs) in New Zealand are mainly salaried and belong to primary health organizations (PHOs), with compensation being derived from two main sources of income: 1. Capitated government-determined compensation; and 2. Patient copayments. In the Canterbury District Health Board (CDHB), for example, these copayments may range from $40-$50/visit during regular office hours and $75/visit during out-of-hours as part of the CDHB’s desire to offer 24-hour access to primary care. Children are excluded from copayment model.

Variable PCP copayments across New Zealand are generally accepted as the status quo and are a source of inequity in the system. Is this something we would consider in Ontario? For example, what would co-pays for access to a family doctor in affluent Toronto neighbourhoods in Rosedale or Forest Hill look like in comparison to neighborhoods with lower income brackets?

In the Spring 2019 issue entitled The Geography of Difference, The Local revealed important data with respect to the fact that Family Health Teams are often located in Toronto’s higher income neighbourhoods. It’s not difficult to imagine how this would be further exacerbated with the introduction of variable co-pays.

With respect to PCP compensation and average hours worked, the following are results from a survey of over 2500 PCPs conducted by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practice (RNZCGP) in 2017:

- The median income for a PCP in New Zealand is between $100,000 and $125,000 (approx. $87,000–$110,000 CDN), with a quarter earning over $200,000 (approx. $175,000 CDN) and 18 per cent earning less than $75,000 (approx. $65,000 CDN).

- The average number of hours worked by PCPs was 35.2 hours. Just over half (54 per cent) of PCPs worked full-time and 46 per cent worked part-time (defined as working fewer than 36 hours per week).

By comparison, the average gross clinical payment for a family physician in Canada in 2016-2017 was $277,000, according to the Canadian Institutes for Health Information. Interestingly enough, the RNZCGP survey also noted that nearly half of respondents indicated that patients in their practices frequently deferred appointments because of the cost of co-pay, and this rose to 81 per cent in high needs areas. This is important to consider when we examine the perceived success of the Canterbury integrated model of care and the socio-economic factors that may influence Canterbury’s care delivery model.

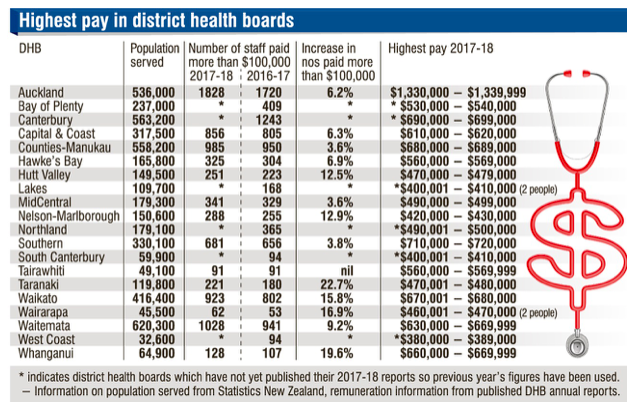

Specialists in New Zealand are employed by the DHBs and are salaried for their services in the public domain. According to the OECD Health Care Resources: Remuneration of health professionals, in 2017 specialists in New Zealand were compensated $131,745 (salaried income, $US PPP). Remuneration information gleaned from DHB annual reports indicates the highest pay band (2017–2018) for Canterbury to be $690,000–$699,000, with two other DHBs reflecting higher top billers (Bay of Plenty and Auckland).

Highest pay in District Health Boards. Source: Otago Daily Times

Highest pay in District Health Boards. Source: Otago Daily Times

Similar to other health systems we have studied (Australia particularly), there is an active private sector in New Zealand whereby specialists are allowed to supplement their public sector income on a fee-for-service basis. As has been shown to be the case in Australia and the UK, individuals with private health insurance in New Zealand receive care faster for elective procedures and are also able to jump the queue in the public system through private referral. The relative success of the private sector in New Zealand is very much dependent on where one lives and the local population’s ability to pay. Similar to other universal public health systems that have introduced private pay models, the more complex cases (and resulting higher costs) are generally left to the public system while relatively easier elective procedures are done in the private sector.

In The numbers don’t lie: how inequality is baked into the NZ health system Carl Shuker and Robin Gauld provide important insights on how certain aspects of the private health sector operate in New Zealand, specifically with respect to queue jumping and manipulating a patient’s needs against national criteria so that patients with private pay can also receive care faster in the public sector with the support of private specialist assessment. According to the Commonwealth Fund’s health system profile of New Zealand, approximately 33% of the population purchased private insurance and private pay accounts for about 5% of total health expenditures.

Pharmacare and Wait times for Common Procedures

With respect to medications, inpatient and outpatient prescription drugs are included in the national drug formulary. Similar to what Dr. Eric Hoskins has proposed in the the Final Report of the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare, New Zealanders are subject to small copays (usually $5) on drugs for each subsidized prescription medicine. The Pharmaceutical Management Agency (Pharmac) decides on what medicines and pharmaceutical products are subsidized for use in the community and public hospitals, similar to what the proposed new national drug agency would do in Canada, including negotiating prices and creating a formulary of approved, covered drugs.

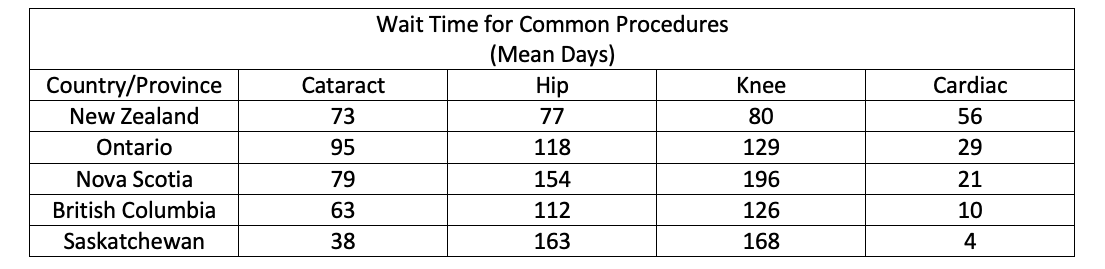

When we examine wait times for common procedures in New Zealand and Canada, there is considerable difference in wait times with respect to knee and hip replacement times while Canada does comparably well with respect to cataract and cardiac wait times.

The Canterbury Health System

As we have referenced in a previous health system blog on Kaiser Permanente, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care directed Ontario Health Team applicants to a jurisdictional scan with suggested integrated care systems as models of success to consider replicating. The Canterbury care model covering Christchurch and surrounding areas on the South Island made the list of recommended models.

The Canterbury District Health Board (CDHB) serves a population of approximately 565,000 people and directly employs around 10,000 staff. Similar to the LHIN model of care, the CDHB receives lump sum funding from the Ministry of Health to coordinate health services.

As noted in the King’s Fund Report (Developing Accountable Care Systems: Lessons from Canterbury, New Zealand) authored by Anna Charles, compared with the rest of New Zealand, “Canterbury has lower acute medical admission rates; lower acute readmission rates; shorter average length of stay; lower emergency department attendances; higher spending on community-based services; and lower spending on emergency hospital care”.

While the Canterbury model of integrated care has been undergoing significant transformation for quite some time, many observers have suggested that major change was initiated by the devastating earthquakes that struck New Zealand in 2010 and 2011.

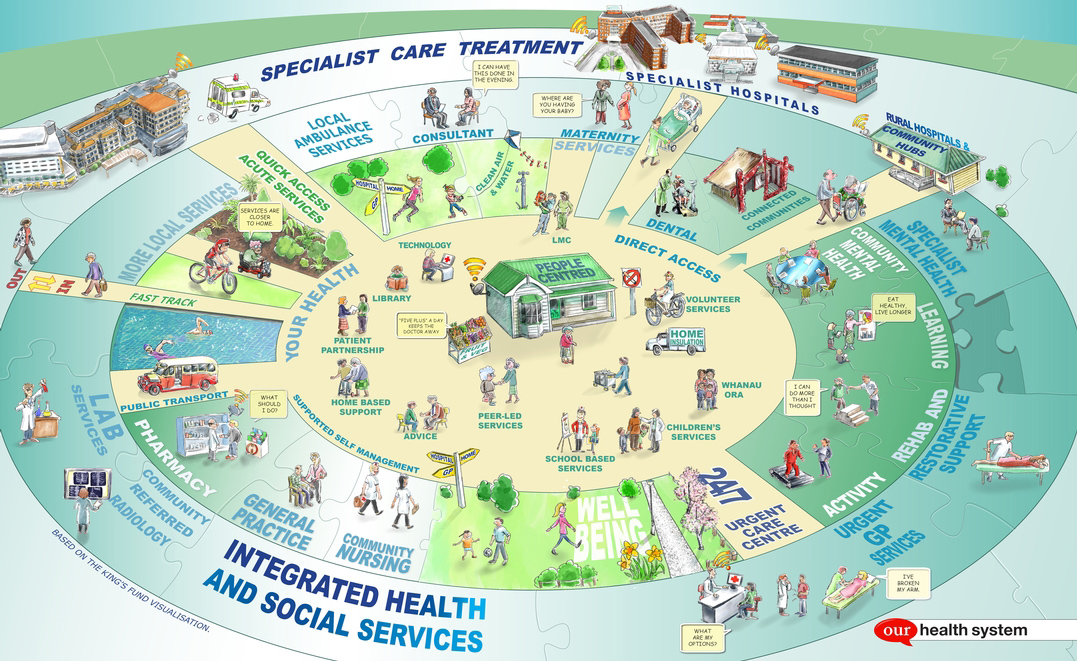

In the aftermath of the earthquakes, it became glaringly apparent that the CDHB lacked a model of care that provided continuity of services between primary care providers, hospital specialists, and community care services such as long-term care and rehabilitation. As a result, comprehensive consultation was undertaken across all levels of health care delivery in an effort to properly realign the health system such that care was delivered with the patient at the centre – a ‘one budget/one model of care’ concept, as depicted below.

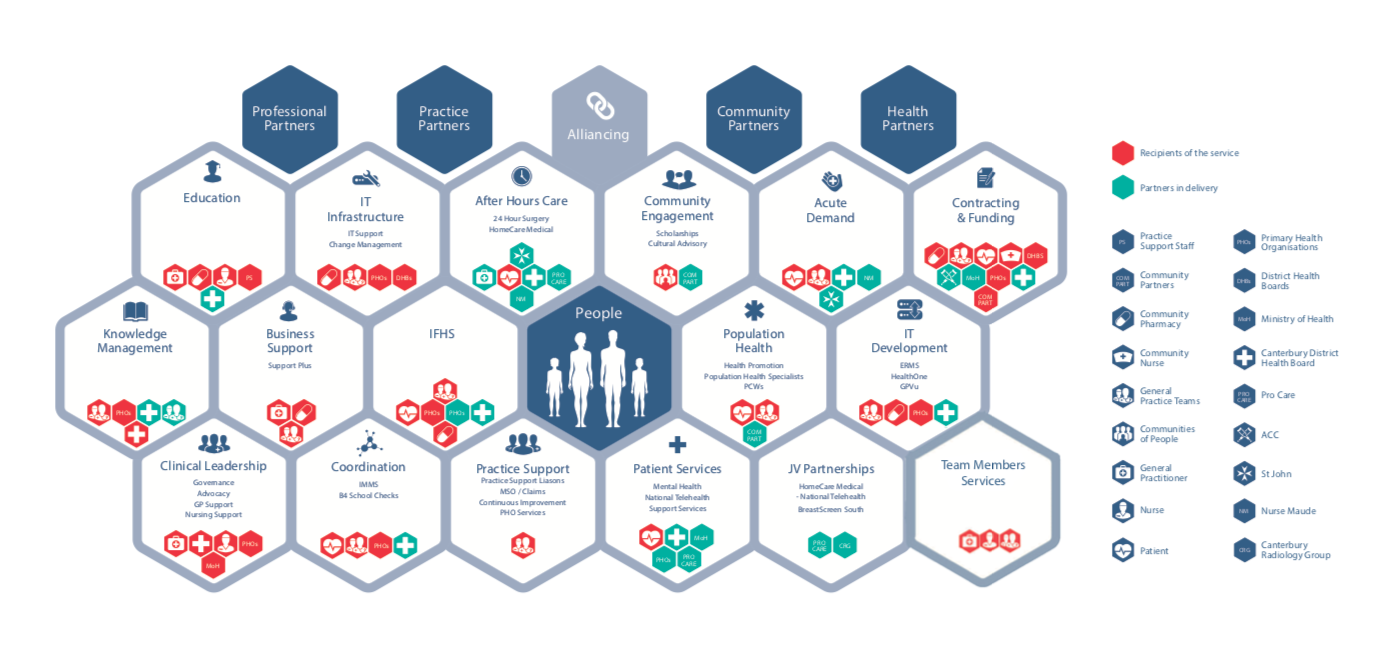

Pictogram of health care system in Canterbury. Source: The quest for integrated health and social care. A case study in Canterbury, New Zealand. Nicholas Timmins and Chris Ham

The vision that Canterbury developed was a single, integrated health and social care system where people work together around the needs of patients. The Canterbury model is fundamentally rooted in primary care, including 24-hour PCP service. General practice clinics staffed with PCPs, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and allied health professionals work together to provide more integrated care.

In New Zealand, these Primary Health Organizations (PHOs) are responsible for ensuring provision of essential primary health care services to the people that are enrolled. There are currently 31 separate PHOs in New Zealand. Within the CDHB, Pegasus Health is the largest PHO with over 445,000 rostered patients and is responsible for ensuring that continuity between primary and hospital-based care. Pegasus offers 24-hour clinics that are staffed by local PCPs, including a 5-bed observation unit, X-rays, bloods and a range of other diagnostic tests. The diagram below demonstrates the variety of services that Pegasus offers to support the delivery of primary care in CDHB.

How We Work in the Canterbury Health System. Source: Pegasus partners in health.

How We Work in the Canterbury Health System. Source: Pegasus partners in health.

In Towards integrated person-centred healthcare – the Canterbury journey Carolyn Gullery and Greg Hamilton describe three positive measurable impacts as a result of the Canterbury model of integrated care:

- Acute admission reduction: Through an acute care management program, PCPs are provided resources to provide acute care in the community setting with support from community-based providers and hospital-based specialist advice. In this manner, more responsibility is downloaded to community providers such that acute patients are triaged more appropriately for specialist referral to a hospital. Perhaps this model has been met with success due to both PCPs and specialists being on a salaried model, such that there is no incentive through the fee-for-service mode to provide treatment that may be unnecessary. Freeing up secondary care-based specialist resources to be responsive to episodic events, more complex cases, and the provision of advice and support to primary and community care has been successful.

- Reducing length of stay: More timely discharge with community rehab services has enabled shorter hospital stay. This is supported by a Community Rehabilitation Enhancement Support Team (a wraparound, home-based rehabilitation program for older people post-discharge).

- Reduction in aged residential care: Proportion of people over 75 years of age living in care homes has fallen from approximately 16% to 12% over past 7 years with a focused effort to care for people in their homes.

To provide a further foundation for continuous care and system integration between community providers and hospital specialists, Canterbury has adopted HealthPathways, a comprehensive system of agreed upon primary care management and referral pathways. Jointly developed by hospitals and PCPs, close to 700 pathways of care have been developed by primary care and hospital teams to provide assessment, management, referral, and patient information and reference material. According to Gullery and Hamilton, the HealthPathways referral system has “contributed to a 43% increase in population access to elective surgery and saved millions of days of waiting time”.

Could a set of highly applied and detailed local agreements on best practice be a model for Ontario Health Teams to consider? Would there be enough collective clinical leadership present in each OHT to create such a system to improve practice and patient outcomes? Would it be appropriate to develop one set of care pathways for the province or does each region require distinctive protocols?

Gullery and Hamilton also note the creation of alliance contracting for health services in Canterbury as a key enabler to system integration. The Canterbury Clinical Network is the broadest health alliance in New Zealand with 12 partner organizations. In the concept of alliance contracting, health partners in the system work together to balance the best interests of the local population with what is best for the sustainability of the Canterbury health system. It assumes that multiple health partners can achieve better outcomes by working together on agreed upon contracts in which everyone wins, or everyone loses. Governance frameworks and key performance indicators include a shared commitment to relevant population-based funding and efficient service delivery.

Can the Canterbury model work in Ontario?

When we try to analyze the Canterbury model insofar as its applicability to the Ontario health system, and whether not we should advocate for adopting such a model, perhaps we can refer back to the Commonwealth rankings to ask some important questions. Because the Canterbury District Health Board is the second largest DHB in New Zealand by both geographical area and population size – 12% of the New Zealand population and covering 26,881 square kilometres – we can safely assume that some of the Commonwealth survey data is gleaned from the CDHB population.

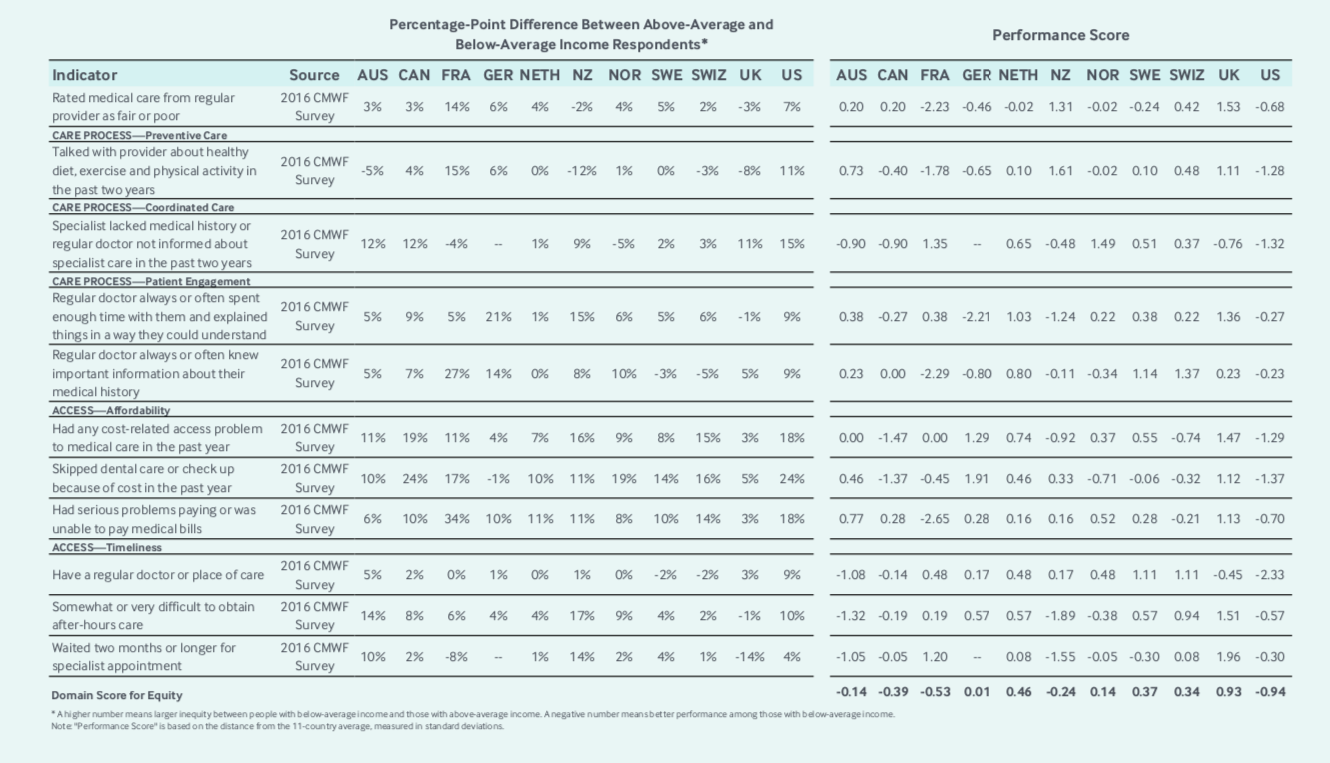

While New Zealand ranked ahead of Canada in the overall Commonwealth rankings (4 vs. 9), it is telling to look specifically at the equity rankings, where Canada and New Zealand placed 9 and 8, respectively.

Appendix 5: Equity. Source: Commonwealth Fund eleven-country summary scores on health system performance.

Appendix 5: Equity. Source: Commonwealth Fund eleven-country summary scores on health system performance.

As we have noted in a previous entry looking at the NHS, Canada’s scores with respect to affordability would be higher if we had universally funded pharmacare and dental care. Surprisingly, after describing the merits of Canterbury’s integrated care system, New Zealand received poor grades with respect to the following equity measures:

- Coordinated Care: Specialist lacked medical history or regular doctor not informed about specialist care in the past two years.

- Patient Engagement: Regular doctor always or often spent enough time with them and explained things in a way they could understand.

- Affordability: Had any cost-related access problem to medical care in the past year.

- Timeliness: Somewhat or very difficult to obtain after-hours care.

- Timeliness: Waited two months or longer for specialist appointment.

It should be noted that the information used by the Commonwealth is overwhelmingly derived from surveys of patients and providers (about 90% of indicators are survey-based). We have described the potential pitfalls of this system in previous blogs whereby the selection of respondents would potentially skew results (e.g. – if the Commonwealth survey for Australia (ranked #2) had a high proportion of responses from privately insured patients or private hospital providers, the results for the country could be skewed dramatically in a positive direction).

What important questions can we ask of New Zealand’s system (and perhaps the Canterbury model) if they perform poorly with respect to equity measures? Is cost-related poor access caused by PCP co-pays?

Jacqueline Cumming, Director of the Health Services Research Centre and a Professor in the Faculty of Health at Victoria University of Wellington, speaks to significant inequities in the New Zealand health system in this health policy piece in Policy Quarterly. On pg. 15, Professor Cumming notes that co-pays result in alarmingly high rates of unmet need for primary health care. The Commonwealth findings also seem to contradict the Canterbury model claims with respect to access to specialist care and the availability of after-hours care – New Zealand received the worst two scores in this regard.

Perhaps Canterbury is an outlier from other DHBs, but then the question must be asked: If CDHB is an outlier and these scores do not accurately reflect their model of care, why then is every other DHB in New Zealand not adopting the Canterbury model?

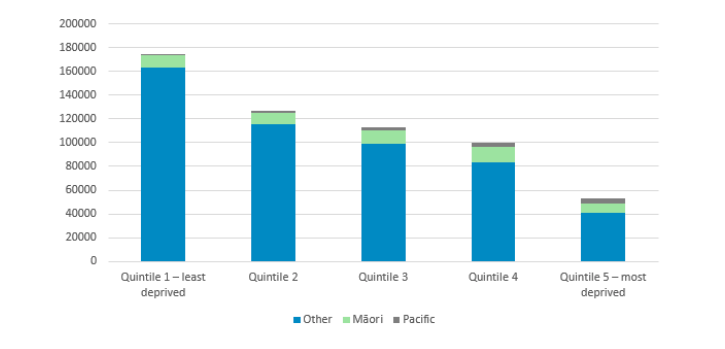

It might also be worth looking at the demographics of the CDHB when seeking information on how this model would help inform the Ontario Health Team model. According to New Zealand Ministry of Health data, CDHB has a relatively high proportion of people in the least deprived section of the population, while the most deprived section is under-represented.

Canterbury District Health Board – Deprivation 2018/2019. Source: Population of Canterbury DHB.

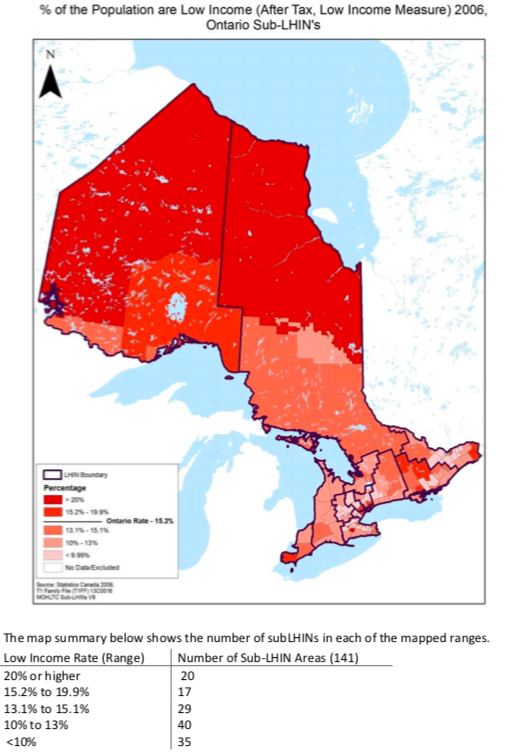

Observing this data, and comparing it to the below map from a Demographic Analysis of Ontario’s Sub-LHIN Populations by Dianne Patychuk and Katherine Smith examining low Income rates for sub-LHINs in Ontario, it may be necessary to ask how (and where) the Canterbury model of integrated care would apply in an Ontario health care setting with the introduction of Ontario Health Teams.

Low Income based on After Tax Low Income Measures 2006. Source: Demographic Analysis of Ontario’s Sub-LHIN Populations. Dianne Patychuk and Katherine Smith.

As C.D. Howe Institute Fellow Will Falk recently pointed out on social media with respect to thoughts on Ontario funding reform: 1. The word population is ambiguous. It is being interpreted (at least) in two different ways – diseased based bundled funding and geographic capitation; 2. Geographic capitation appears to be the longer-term basis for the OHT reform but will take several years to reach implementation even in the early adopters; and 3. Disease-based bundle funding will be implemented in the current system and may be an interim step for moving to full geographic capitation.

These are important points to consider as we examine the Canterbury model and its potential applicability in Ontario. Certainly, the Canterbury model via geographic capitation would work well in high-income areas of Toronto whereby residents could afford the necessary co-pays and readily access other bundled services as per the Canterbury model. Likewise, it would perhaps be easier for providers in high density areas to form alliances and HealhPathways referral methodologies than it would be for more remote regions of the province.

In general, the socio-economic characteristics of the CDHB do not reflect that of Ontario – perhaps that is a reason the Canterbury model has not been adopted widely in other parts of New Zealand? It is worthwhile referring to Shuker and Gauld’s piece once again on how service inequity is baked into the New Zealand health system to reflect on the wider applicability of the Canterbury model.

Importantly, as we have also noted in a previous blog on Kaiser Permanente, retaining autonomy is an important issue for Ontario physicians and will likely be an important factor in achieving success with the Ontario Health Teams. Would both specialists and primary care providers be willing to accept a salaried model for their services? Would the general public be in favour of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care contracting with private clinics to provide elective procedures in Ontario as the DHBs do in New Zealand? By definition, contracting with private providers for publicly funded care requires acceptance of a two-tiered system based on ability to pay.

Lastly, much has been made about the bloated bureaucracy in Ontario’s health system, and the transition in government messaging from “not one job will be lost” to “not one front-line job will be lost”. The question must be asked: Who will govern and administer OHTs given that this transition will likely involve substantial challenges – both organizational and procedural?

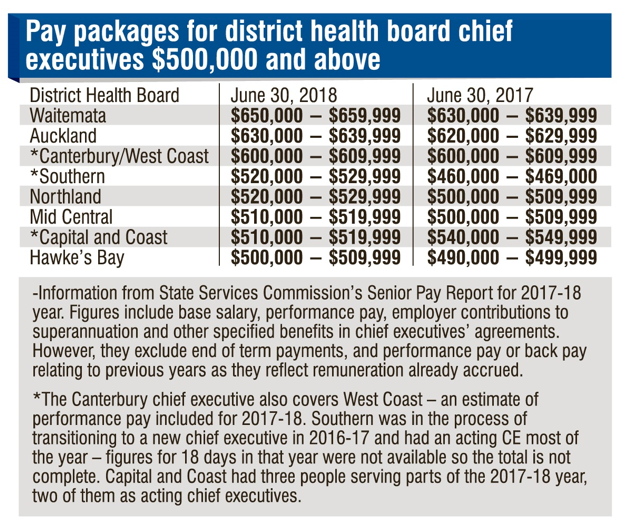

It is clear from examining the Canterbury District Health Board (and the other 19 DHBs in New Zealand) that administration is required to run an integrated health system. Furthermore, within the Canterbury model, Pegasus Health (primary care PHO) has its own sophisticated governance structure separate from the CDHB leadership team. Notably, eight DHB executives were compensated $500,000-plus in the 2017–2018 financial year, with Canterbury’s chief executive officer, David Meates, reportedly earning between $600,000–$609,999.

Pay packages for District Health Board chief executives $500,000 and above. Source: Otago Daily Times.

As the guidance documents from the Ontario government have no clear direction on governance, this will be an important question to consider in the formation of OHTs. If they are to be primary care driven, PCPs will absolutely need to participate in their administration – the question remains whether or not OHTs will receive funding to do so or if PCPs will be responsible for overseeing these arrangements themselves without administrative funding.

Using the comparative framework of governance and administrative structure, the Canterbury model seems more representative of a LHIN rather than the proposed OHT. LHINs were led by boards, as are the DHBs in New Zealand. LHINs had a small number of administrative workers responsible for ensuring that funding was used appropriately by health care providers. Under the Patients First Act LHINs were responsible for regional organization of homecare, mental health services and for integration of primary care, similar to the governance model of the Canterbury system. At present, it is not clear how the services in OHTs will be governed or administered.

What important lessons can we learn from the Canterbury model? It certainly makes the case (although quantitative comparable data cannot be found) that Ontario health care will be better served by migrating away from hospital-centric care to a model where primary care is at the centre of care organization. In theory, this will better meet the needs of a definable population and may be more financially sustainable, as evidenced by the large deficits CDHB was operating at prior to embracing a new model of integrated care. Furthermore, a centralized referral pathway system for each OHT (preferably supported by e-referral and e-consult), similar to CDHB’s HealthPathways, will provide for consensus clinical guidance for PCPs and hospital clinicians in each OHT and foster new ways of working together to deliver care.

Perhaps most important to recognize is that the evolution of the Canterbury model did not happen overnight – it has taken substantial investment of time and money to come to fruition. There are still many questions left unanswered with respect to the governance, leadership and operational capacity of Ontario Health Teams. If the introduction of OHTs is intended to cut costs by reducing administration, it will likely not be met with success.

The Canterbury Tales is generally thought to have been incomplete at the end of Chaucer’s life. His original plan was to write over 100 stories as part of the collection but he only wrote 24. Whether or not this current government remains in power beyond the end of its first mandate in 2022, the OHTs it initially selects to transform the province’s healthcare system will be writing their own health care tales for decades to come based on this system overhaul. Hopefully the government will provide OHTs with the foundational resources necessary to ensure that the OHT model of integrated care is a tale of success.