Written by Dr. Boris Kralj

Earlier this year I wrote about the growing shift in the gender composition of the Canadian physician workforce and the unexplained large gap in earnings between male and female doctors.

While the feminization of the physician workforce has been well documented and discussed, another shift has also taken place which has not been very well recognized in the typical analysis of physician profiles. Both shifts are a reflection of our population at large, and both have potential implications for the provincial medical associations that represent physicians in pay negotiations and serve some of their other professional needs.

The composition of the Canadian physician workforce in terms of visible minority (non-white) composition has changed noticeably over the past couple of decades (refer to figures below). ‘Visible minority’ refers to whether a person belongs to a visible minority group as defined by the Employment Equity Act, and if so, the visible minority group to which the person belongs. The Employment Equity Act defines visible minorities as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour”. This is the definition employed by Statistics Canada. The visible minority or ethnicity of Canada’s physicians is not something that has been readily available or reported by organizations such as CIHI, that publish data usually limited to basic demographics of specialty, age and gender. Most, if not all, provincial medical association internal membership data bases fail to capture such information also.

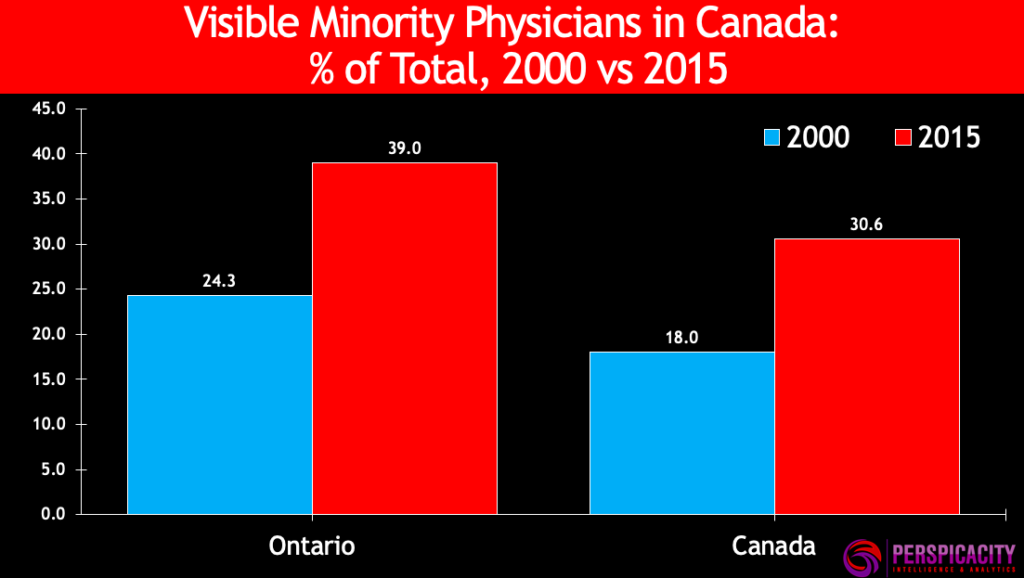

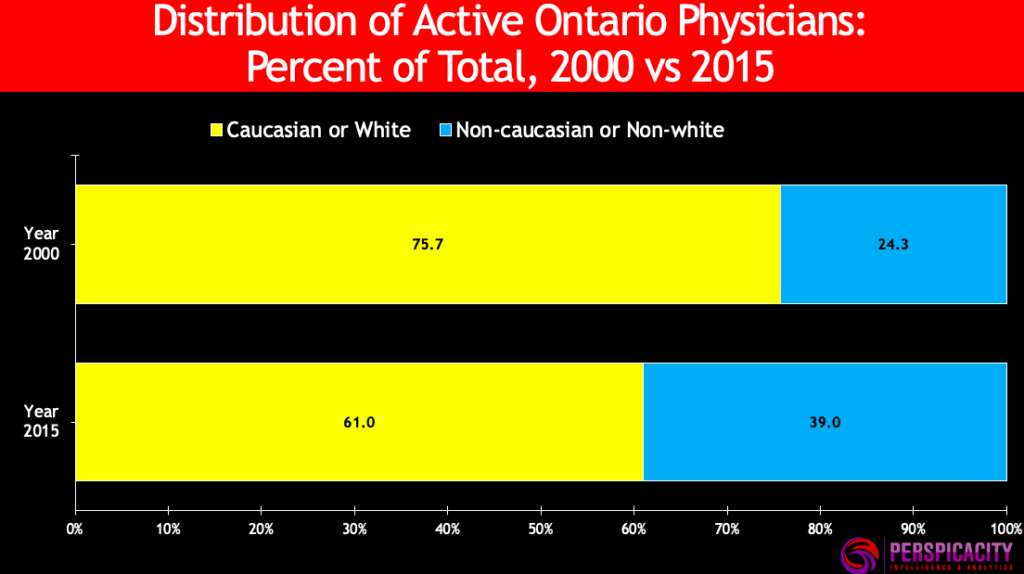

In 2000, 18 percent of Canada’s active physicians were visible minorities; by 2015 that share had risen to about 31 percent. In Ontario, the corresponding increase was from 24 percent to 39 percent.

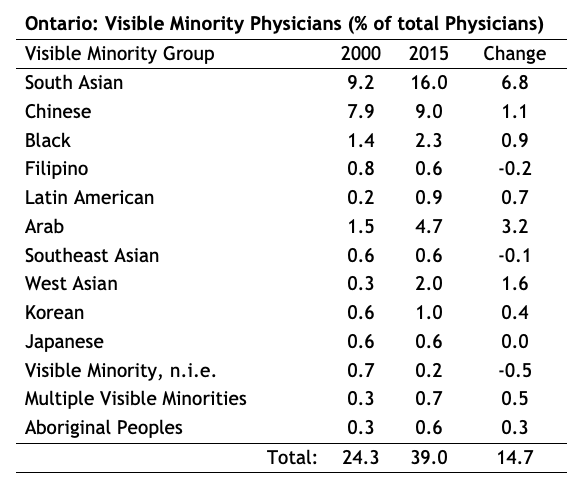

The increase in visible minority physicians has not been even or uniform across all jurisdictions or minority groups. For example, in Ontario most of the increase has come from two groups, the South Asian and Arab groups. See table below.

Typically, most assessments of work effort available at the individual physician level are based on raw billing data and relate to the number of services provided, patients seen, days billed, etc. but do not capture the time (hours of work) to provide services.

I compared the work effort and earnings of visible minority physicians and white physicians in Ontario and Canada overall for the calendar year 2015. Work effort is measured by weeks worked per year, hours worked per week, and annual hours worked as collected by the 2016 Census of Canada. The analysis indicates that there is no difference in any of these measures of work effort between white and visible minority physicians. For example, for Canada, annual hours worked by white and visible minority physicians were 2,278 hours and 2,284 hours respectively. In the physician sector, income data is generally difficult to obtain and usually limited to gross billings that need to be adjusted for overhead costs to get a measure of physician income. The overhead ratios typically come from sample surveys that suffer from low response rates and many other potential biases associated with the survey.

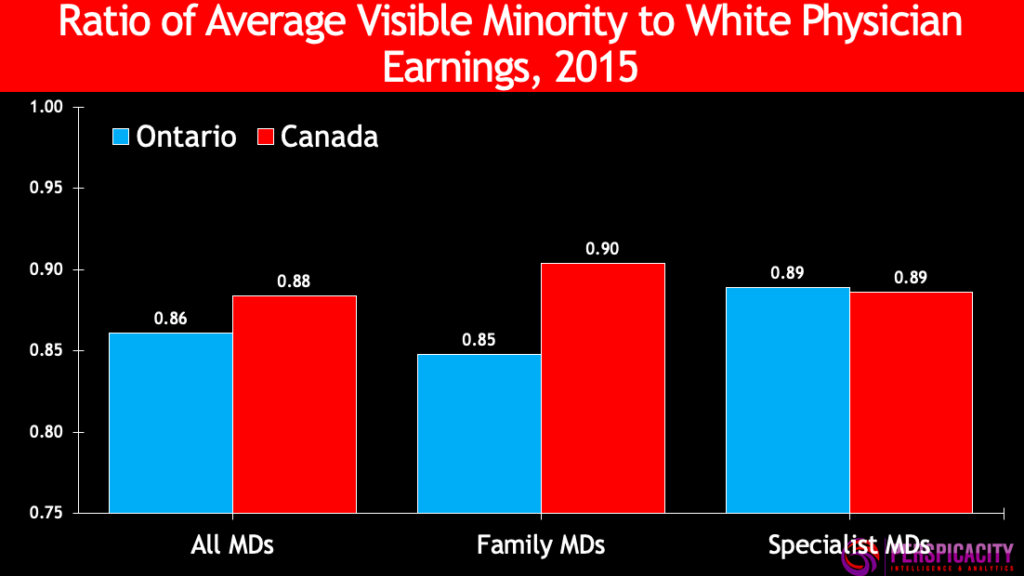

While there is no difference in hours worked, there are significant differences in average earnings (net of overhead expenses) between these two groups. Specifically, the earnings of visible minority physicians are 10 to 15 percent lower, depending on specialty. Earnings (net of overhead expenses) are from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) administrative tax and benefits records of individual physicians for the 2015 tax year, rather than overall specialty averages obtained via self-reported surveys. Linked Census of Canada and CRA micro data for individual physicians was accessed through the Statistics Canada Research Data Centre (RDC) at McMaster University.

This gap in earnings is larger in Ontario than in the nation overall, with visible minority physicians earning only 86 percent of white physician earnings. The gap is especially pronounced for Ontario family physicians. Refer to chart below.

As in the case of female physician earnings being much lower than the gap in work effort, a similar gap persists across visible minority physicians. In other sectors of the economy, gaps in earnings that cannot be dismissed by work effort comparisons are often attributed to “bias” or “discrimination”. Furthermore, efforts via policy, regulations, human rights, etc. are made to eliminate or at least minimize any such bias or gaps and establish pay equity. However, in medicine in Canada there is no action on any front to address these unwarranted pay differences. These issues are not even recognized by the provincial medical associations that represent physicians and that negotiate and allocate their funding. The provincial governments — the payers — are equally missing in action.

A critical fact is that nobody is examining or studying the issue, which is both surprising and alarming given the growth in the shares of visible minority physicians, as well as female physicians, in the Canadian medical workforce.

There is always much discussion and debate on disparities in pay across specialties as well as within specialties. These are the topics captured under the “relativity” banner that have plagued many provincial medical associations for decades. However, these discussions never include the observed disparity in pay between male/female or white/visible minority physicians. This is an issue that has been obscured by the medical profession’s, (via provincial medical associations) traditional focus on inter-specialty relativity. Other inequities such as those based on gender and visible minority status have been and continue to be ignored, cast aside as “collateral damage”, unnoticed in the relativity battles that are still being waged based on methodologies developed before any of these significant demographic shifts in medical workforce composition occurred.

It’s time for the representative bodies of physicians, and the payers, to wake up and smell the coffee and seriously begin to address these other inequities.

Boris Kralj (PhD) is the founder and principal consultant with Perspicacity Intelligence & Analytics. He is also a lecturer at the McMaster University Department of Economics. Follow him on Twitter: @BorisKraljPhD

Image Credit: ©Leaf – Can Stock Photo Inc.