Written by Peter Ellis

Devolution

Last year, as Covid-19 took hold, it became clear why, as a country, our poor performance in managing the pandemic was to be anticipated. Historic structural and cultural barriers within the NHS, the ‘one size fits all’ mentality of Whitehall, and the ‘blame-game’ culture of politics, were several factors that stifled innovation and success.

After a much-delayed call to action, we had a brief respite and a reduction in both deaths and cases during the spring months. Rather than seize the opportunity this presented, the lobbyists within government met it with a laissez-faire attitude, believing that herd immunity would be best for the economy. There have since been two further surges, in the autumn and after Christmas, thus crystallising the UK’s unwanted status as the country with the highest mortality rate among major OECD nations.

This 3rd surge in the pandemic has been by far the worst in both total number of cases and mortalities. The total number of deaths in the UK (from all causes) for 2020 was 91,000 higher (ONS) than the average of the previous five years. This figure demonstrates the full consequence of the pandemic, as opposed to ‘deaths within 28 days of a covid diagnosis’, as it includes the additional deaths caused by delays and limited access to care.

The figure of deaths from Covid-19 (within 28 days of a positive test) now stands at 124,000. This figure, unfortunately, will likely approach 140,000, or, 180,000 if consequential deaths are included, measured by ONS.

Errors will always occur. But we need to be transparent about them so we can learn and highlight areas to improve; the ‘blame game’ culture, on the other hand, leads to avoidance and obfuscation. That the UK continues to have the worst outcomes among both major European and developed OECD nations, should alert the government to the underlying structural issues.

A recent study by four of the UK’s most respected and non-political, research foundations, pointed out that the UK performs worse than similar countries “on the overall rate at which people die, when medical care should have saved their lives”.

Canada is a good point of reference, as both Canada and the UK have publicly funded health systems. Corrected for its population size, Canada, with 58 percent of the UK’s population, had only 18 percent of the UK’s deaths from Covid-19. Similarly, Germany, with a population 24 percent higher than the UKs, has a death toll 45 percent lower.

Canada and Germany, with federation origins, allow their respective provinces and states to develop their own health care (along with education and economic development). The UK on the other hand, with the world’s largest healthcare delivery system managed as a single entity (NHS England), grants devolved responsibility to Scotland (5.4 million population), Wales (3.15 million) and Northern Ireland (1.9 million), but denies them to Yorkshire and Humberside (5.4 million).

Regional differences

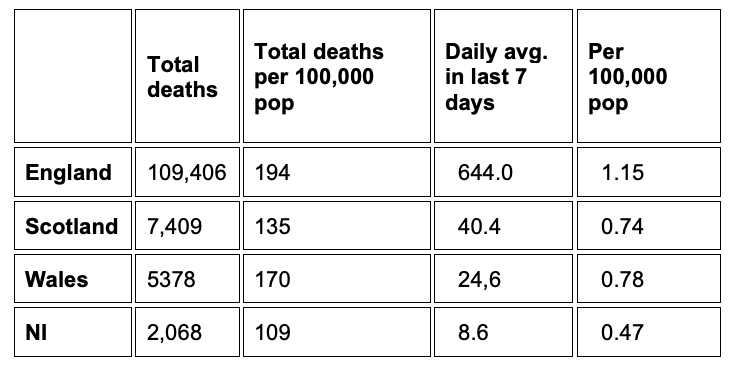

As this chart shows, deaths as of 5 March2021 by all the devolved countries, indicate superior performance for all devolved regional systems, where public health, primary, secondary and long-term care are better integrated.

‘England’ is not a homogenous region; it is a heterogeneous mishmash, with many regional differences. For boys born in the UK 2016–2018, the gap between towns of healthy life expectancy is profound: 71.9 years in Richmond upon Thames, compared with 53.3 years in Blackpool, a gap of 18.6 years, which has increased by five years since 2009. The figure for women is similar.

When averaged out across the nine English regions, the variations are naturally less dramatic, but still show a variation of over six years between the best and worst regions. Areas of low healthy life expectancy tend to be clustered around South Wales, Eastern Scotland, Northern Ireland, West Midlands and the North of England.

The causes and determinants of this disparity have remained unaddressed, such as the socio-economic status, ethnicity, parental behaviour, and education. There has also been a resistance to any form of real devolution or decentralisation within England.

It is somewhat ironic that the ‘red wall’ – the traditional labour constituencies that swung to Tories – has a reduced longevity of healthy life years. These seats were won by the Conservatives not because of a significant increase in votes, but because disgruntled labour voters looked elsewhere. Thus, with the next election in sight, if these huge regional variations continue to grow, it’s where the election will be won or lost.

Regional variation issues extend beyond healthy life years, namely among minority ethnic groups. A recent study by Edinburgh University, involving 27 academic and public health institutions across the UK, showed that out of 1,000 white people needing hospital treatment for Covid-19, 290 died, whereas 350 out of every 1,000 South Asian people died. The study revealed that around 40 percent of South Asian patients had either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, compared with only 25 percent of white groups.

The folly of our homogenous approach is a causal factor in the poor performance of our health care system, and ultimately a major contributor to our excessive mortality rates.

Hancock’s White Paper

Matt Hancock has recently announced a reversal of some of the Cameron-era NHS legislation, hoping to join up local health authorities and the NHS, while at the same time proposing more accountability to central government – an oxymoron if ever there was one.

The concept of integrated care organisations (ICOs) was first introduced into the UK in 2007, within Ara Darzi’s NHS Review. In 2010, a report was produced by the Nuffield Trust and Kings Fund, which lamented that although ICOs had been discussed for decades, nothing substantial had actually happened.

Ten years on, there has been little progress or leadership from the government, the NHS, nor the interest groups (commissioners, primary care, local authorities and hospital trusts). Similarly, the Public Account Committee, as recently as last year continued to recommend devolvement but with little to show for it.

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, in a recent Times article, sums up Hancock’s white paper, suggesting that, “he wants to be able to intervene in local service reconfiguration changes” and determine what happens at local hospitals. Johnson points out that the experience of the past year has somehow led Whitehall to believe they are capable of taking on the NHS.

There is another initiative, a component of the ‘level up strategy’, being considered within government to enable a more regional focus. It would replace the House of Lords with a new second chamber, representing the regions through directly elected ‘senators’. Gordon Brown, the former PM, has also been promoting such a model and it’s believed to have supporters in all parties. It is a great idea but will be likely face a lot of opposition from the Westminster bubble and Little Englanders.

The rationale for a devolved and integrated health and care model has been laid bare by the pandemic. Obesity is recognised as the major cause for diabetes, cancer and heart disease and has been highlighted as the most important determinants of a patient’s recovery/survival from Covid-19. More than a third (35 percent) of adults in the UK are overweight. Figures from the Intensive Care National Audit Research Centre suggest that at least two thirds of people who have fallen seriously ill with coronavirus were overweight or obese.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are related to education, diet, and exercise, and responsibility rests on more than just parents, but on public health interventions and in some instances, psychological treatment. We must therefore manage health, primary care, hospital care and social care through integrated structures with ceded powers, if we are to effectively integrate public health services, NHS, and community care.

Ten years ago, the University of Pittsburgh undertook some research, which concluded that critical to the success of an integrated public health care system, was effective funding and authority to the single entity (in the UK’s case, the NHS). Dr Martin Vernon, former national clinical director for older people, argued in a recent article, “In a truly integrated system, it can be expected that the NHS will need to cede some power in the health sector. This work cannot be driven from the centre of the NHS”.

It is clear the government’s re-election hopes will be dependent on holding on to the red wall seats, which were gifted to them by the disillusioned labour voters with the party’s leadership. As a result, the pressure to deliver on the “level up” promise will be essential. But it cannot be achieved without effective devolution and ceding of power away from Westminster to the regions. Politicians have hopefully realised that holding on to healthcare creates all the flack without any rewards.

One year on and three steps backwards: Covid-19 and the NHS revisited (part 2)

Author’s BIO

Peter Ellis has over 40 years of experience in the strategic development, managing and advising of health organisations in the UK, the Americas and Europe. He is currently an Executive Advisor to SweatCo Ltd, Bio Conscious Technologies and Motilent.

Previously Peter Ellis has led strategic consulting assignments in Pharmaceutical, Private Equity, Biotech, Health IT and Medical Device organizations, as well as for governments, payer and provider organizations.

He was instrumental in the development of the concept of “Academic Health Science Centres” in the UK and advised Imperial College, Kings College, QMUL, The Bart’s and London Hospital and the Darzi review.

Before his return to the UK, Peter Ellis had a long (20+ year) career at Sunnybrook Health Science Centre, Toronto, which he led as President & CEO, through a dramatic period of growth, during its transition from a Veterans Hospital, to an internationally recognised health science centre, specialising in cancer, heart disease, trauma, mental health and care of veterans and the elderly.